Abstract

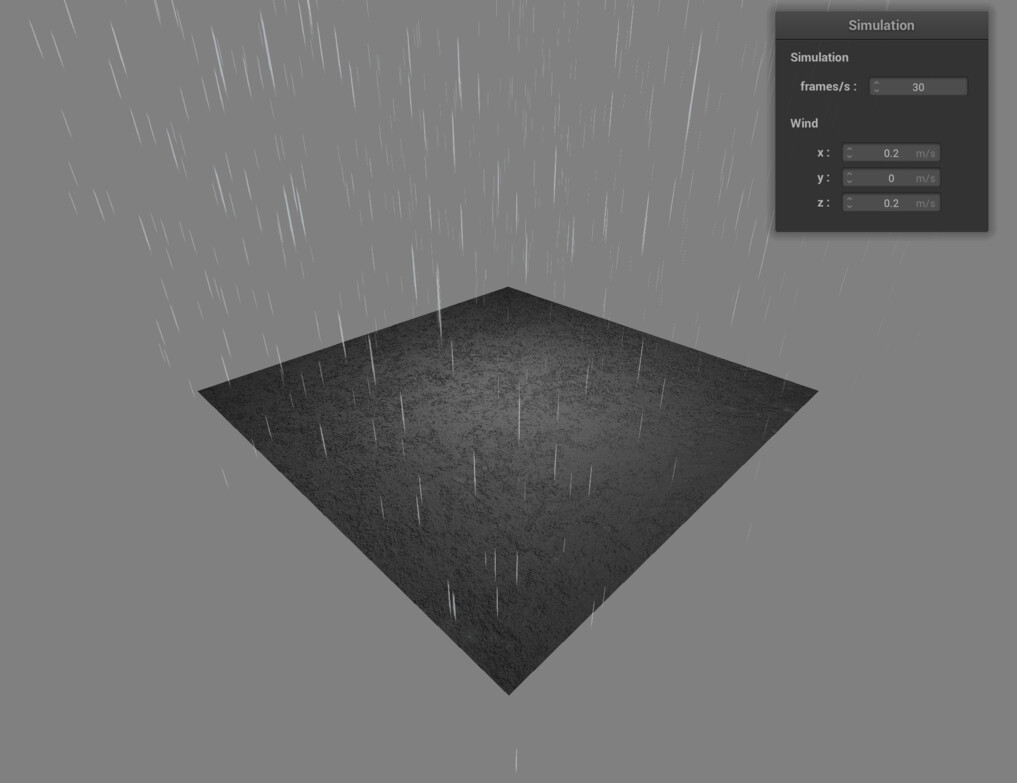

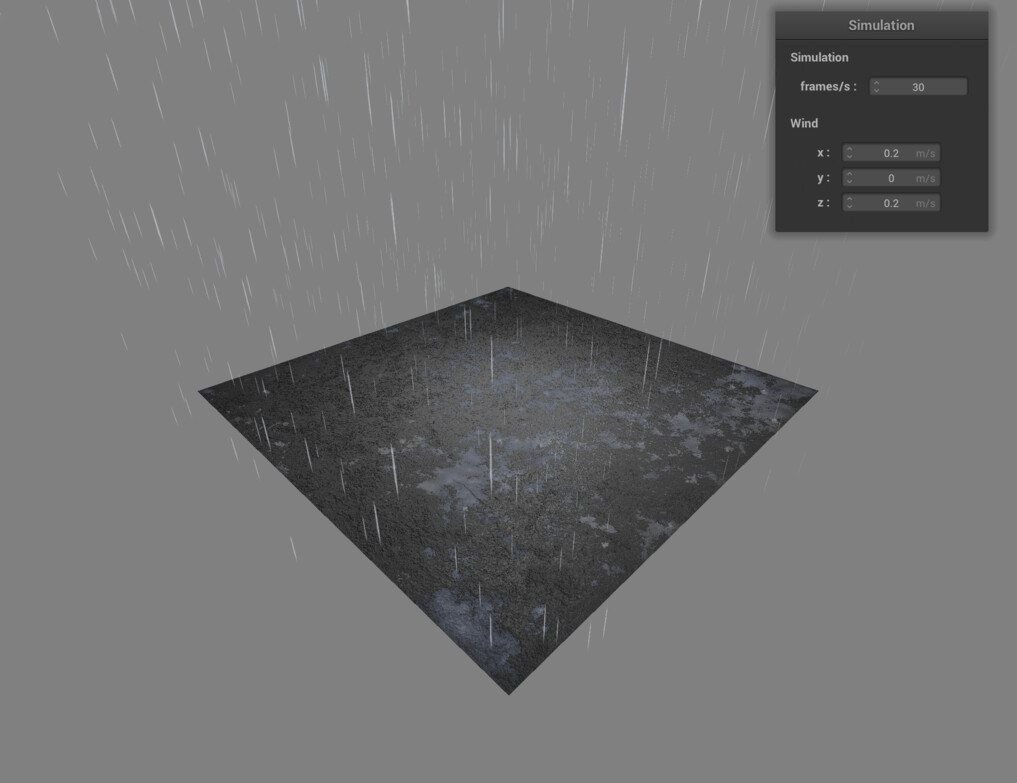

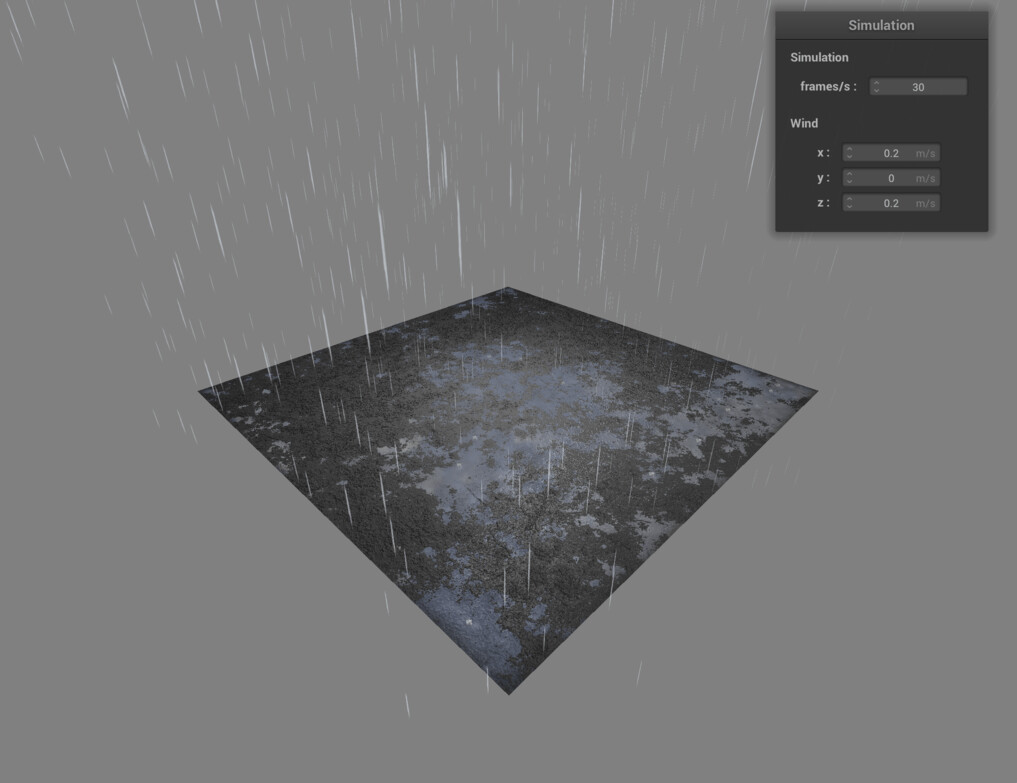

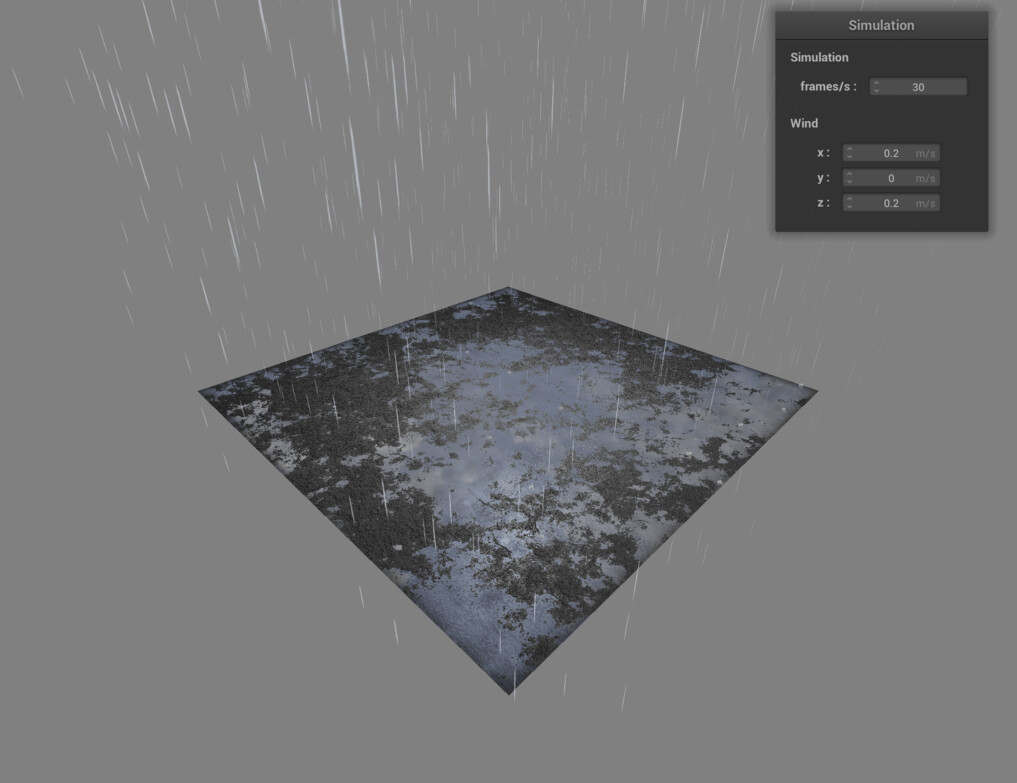

Video games often use rainy scenes to add realism, ambience, and emotion to in-game environments. However, real-time realistic rain rendering is difficult to perform due to its computational and visual complexity. In our project, we implemented a real-time rain simulator in which rain particles fall onto a gravel-like surface, wetting the ground until it begins to show puddles reflecting the scene, on which the rain particles splash. We built upon the Project 4 codebase to make a particle interface in which point-sprite particles fall and collide with the plane, with velocity controlled by variable wind, updating a wetmap with kernel blur upon collision. We used this wetmap to update a dynamically changing texture map sampled by the ground shader. The ground shader used a combination of lambertian shading, phong shading, environmental texture, and bump mapping to generate a realistic surface that mirrored the scene below the ground plane to create the illusion of reflectance. We rendered point-sprite splashes at sites of collision and adjusted their opacity based on the wetmap. Finally, we used parallel computing of the dynamic texture map shading to allow for efficient real-time rendering. In our implementation process, we ran into challenges in debugging shaders, making raster graphics seem realistic, and laggy simulations. We found that using reference images can help in building shaders. For more realistic raster graphics, we took notes from tricks old video-games used. To get around laggy or interrupted simulations, we debugged memory leaks and used parallelism. By building a realistic real-time rain simulator, we learned how to create and map dynamic textures, generate point sprites, implement particle interfaces, and a wide variety of techniques for building more realistic environments.

Technical Approach

Particle Simulation

To generate rainfall, we built a particle interface using a Raindrop class. The Raindrop class contains a raindrop’s position vector and a “hit” vector, which represents the location that the raindrop will eventually hit the ground (starting_position - velocity * (starting_position.y / velocity.y)). Upon initialization of this interface, a set amount of Raindrops are created with their positions set to a random coordinate within a range of coordinates and stored in a vector. Each time step, a simulate function would be called in which each Raindrop’s position would be updated according to a velocity class attribute by looping through the Raindrop vector. A check is made to see if the raindrop collided with the plane (y = 0 and within the x and z bounds of the plane using the hit attribute), and if satisfied, the wetmap is updated at the index that represents the collision location. In addition, a new Raindrop is generated and placed at the starting position. Wind is updated by user input in the UI, which calls an updateWind function that changes the velocity Raindrop class attribute.

Rain Appearance

We render raindrops with a raindrop-shaped texture but without a raindrop-shaped mesh. At first, we tried to render raindrops based on Real-time Rain Simulation, which draw raindrops as point sprites in the screen space. While the appearance of raindrops looks good from a horizontal perspective, it keeps its elliptical shape and doesn't change the orientation of textures when viewing from a vertical perspective.

To achieve more realistic effects, we first bind each raindrop a \(1 \times 1\) quad lying on xy plane, with texture coordinates binded with its four vertices. However, the raindrop texture would not be visible with a single quad if viewing from the cross section of the quad. To ensure the raindrop keeps its appearance correct when viewing from different perspectives, We convert the quad coordinates into a space with its x axis aligned with view space's x axis and its y axis aligned with the direction of the raindrop's velocity in view space. This ensures the texture always faces the camera in view space. Finally, we perform transformations into view space and projection space as usual. In addition, the opacity of each raindrop changes based on their distance from the camera and the light source to make the rainy scene more realistic. Below is a video showing how raindrops change their shapes in different perspectives.

We found creating Phong shading effects on the point-sprites challenging and attempted to use normal maps to generate these lighting effects. However, this proved difficult as the raindrops did not have a mesh. In the end, we averaged opacity effects based on distance from the camera and light source to give the illusion of lighting effects on the raindrops.

Raindrop Splashes

We render splashes as an animation with each frame sampled from the texture below. The texture incorporates a single filmed high-quality milk drop splash sequence (referenced from Artist-Directable Real-Time Rain Rendering in City Environments). Everytime a raindrop collides with the ground, a splash is generated at the collision point with its size randomized to mitigate visual repetition of the same splash textures. We also change the opacity of splashes based on the wetness degree of the ground to trick viewers that no splashes seem to be on the dry ground.

Each splash is rendered as a point splash in the screen space. To do this in OPENGL, we bind a \(1 \times 1\) quad to the splash and translate it to the colliding position in view space. The texture coordinates is rotated based on the normal of the collision point and scaled based on the splash size. Finally, apply projection transformation as usual. Below is a video that shows a closer look at splashes.

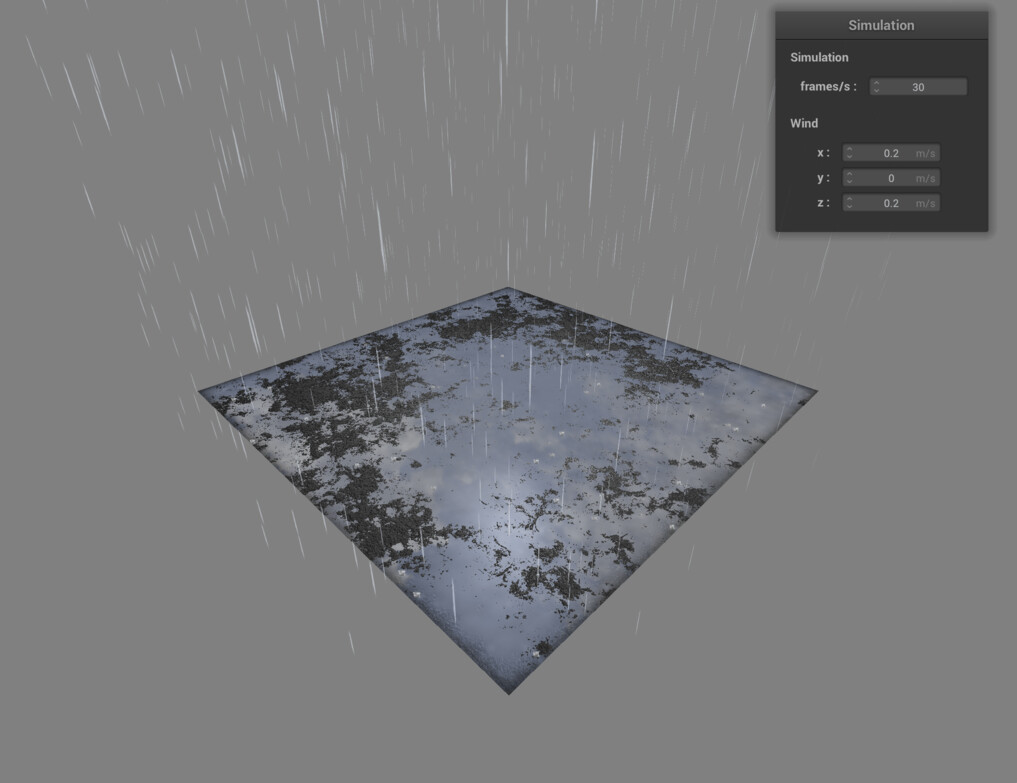

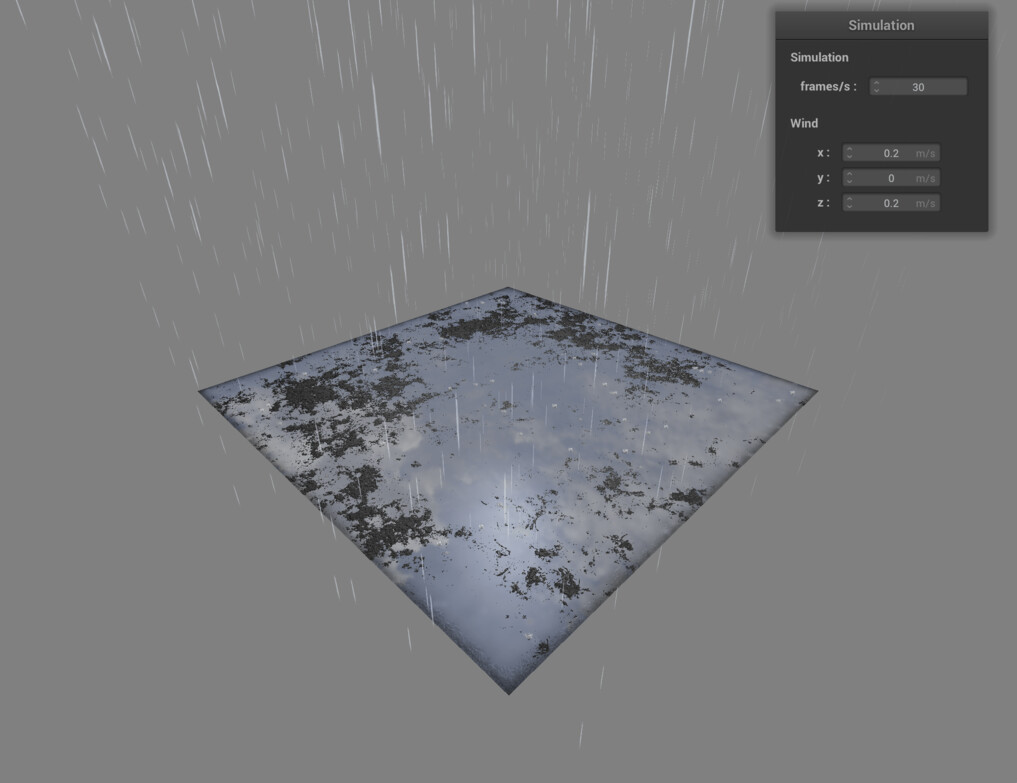

Dynamic Painting

We achieve the illusion of the ground gradually getting wetter by each raindrop using the technique of dynamic painting. With each collision of a raindrop, a pixel on a 2D array gets updated with an increased value. This 2D array is initialized to be a 128x128 square filled with 0's. Higher resolution was really not needed, for a number of reasons. First, the image will be blurred. Second, fragment shaders already sample this image with linear interpolation. Third, as this image is transferred to the GPU every frame, we need to minimize the memory bandwidth footprint.

A particular problem we encountered was the accurate mapping of collision coordinates to UV coordinates. During dynamic painting, it's hard to tell which link went wrong. It could be the collision coordinates that were wrongly calculated, it could be the wrong location in the wet map that was updated, or it could be the process transferring to the GPU being faulty. Debugging mainly consisted of eliminating variables, such as always assigning a corner of the wet map, or using a single particle to hit one place repeatedly.

To simulate the illusion of raindrops gradually spreading out to form puddles, we perform a 3x3 kernel blur on the collision map every once in a while. This blur kernel has a heavy weight on the center pixel, so the spreading out looks natural and gradual. Since the blur kernel is a rank-1 dyad, we could compute the convolution in two separate passes, and we could parallelize the blur process. Further optimizations could be made by leveraging SIMD vector operations, but the performance was already satisfactory enough that we opted to not go any further. The final performance is such that toggling blur on and off made no noticeable difference on simulation speed.

Here's a video demonstrating the dynamic painting and blurring procedure:

This 2D array in memory is then transported to the GPU using the GLTexImage2D function. To increase performance, we try to minimize the amount of data transferred and stored. As a result, we use the data representation GL_RED to send over a monochrome image, 8 bits per pixel. To further facilitate faster transfer times, 4 bytes are transferred at a time. The map is initialized to a multiple of 4 bytes to accommodate that.

A helpful lesson learned was to observe real life: nature is an inspiration for many solutions.

Shaders & Reflections

To make a realistic ground with reflections, a lot of factors are considered. The technical approach is roughly divided into the following sections: ground lighting, reflection tricks and screen space effects.

Ground Lighting

The lighting boils down to a combination of Lambert shading (diffuse), Phong shading (specular), environment texture and bump mapping. The extent they contribute to the overall lighting is mostly based on the height map texture as well as the dynamically-painted wet map. The "wetter" the surface is at a point, the more environment texture and phong shader colors are weighed. The height map input combined with a height "cutoff" variable determines overrides the wetness at a point if the height is beyond the height cutoff: which makes sense since these points are not yet submerged in a puddle. Phong shading however is based on the "raw" wetness, which shows a gloss even at higher positions when they are wet.

Bump mapping is used to show the illusion of a bumpy surface. The fragment shader samples the differential change in heights based on the height map texture at a certain point, computes the normal accordingly, and this normal value is then used as the Lambertian term.

To add the effect of rainwater building up, an additional uniform input to the OpenGL fragment shader is fed from the simulator. This scalar value is proportional to the overall value of the brightness: in fact it's a sampled average of the wet map. This is used as the height cutoff. When the wet map reaches a high average value (i.e. lots of rainwater), the cutoff reaches its maximum and most of the ground becomes reflective.

To give the illusion of a reflection, wet areas of the ground are made partly transparent, especially when there's little gloss or when the environmental texture is darker. The alpha value is determined by the height-corrected wetness and the intensity of Phong/environmental texture outputs. Through the transparent ground, one can then see the mirrored scene imagery on the other side of the ground, which is rendered using tricks described in the next part.

We found it helpful to have a Blender-made reference scene to tune the aesthetics of our final product. By first creating the ground plane, the wet map and reflections in Blender, we took note the roughness and degree of environment texture that looked best.

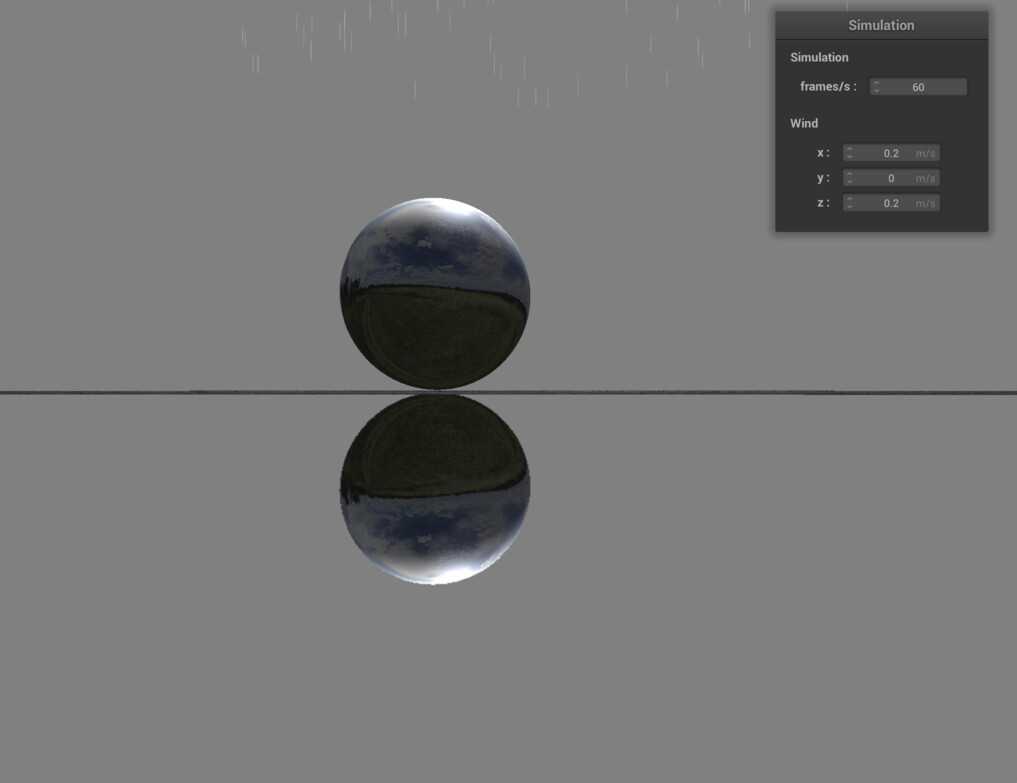

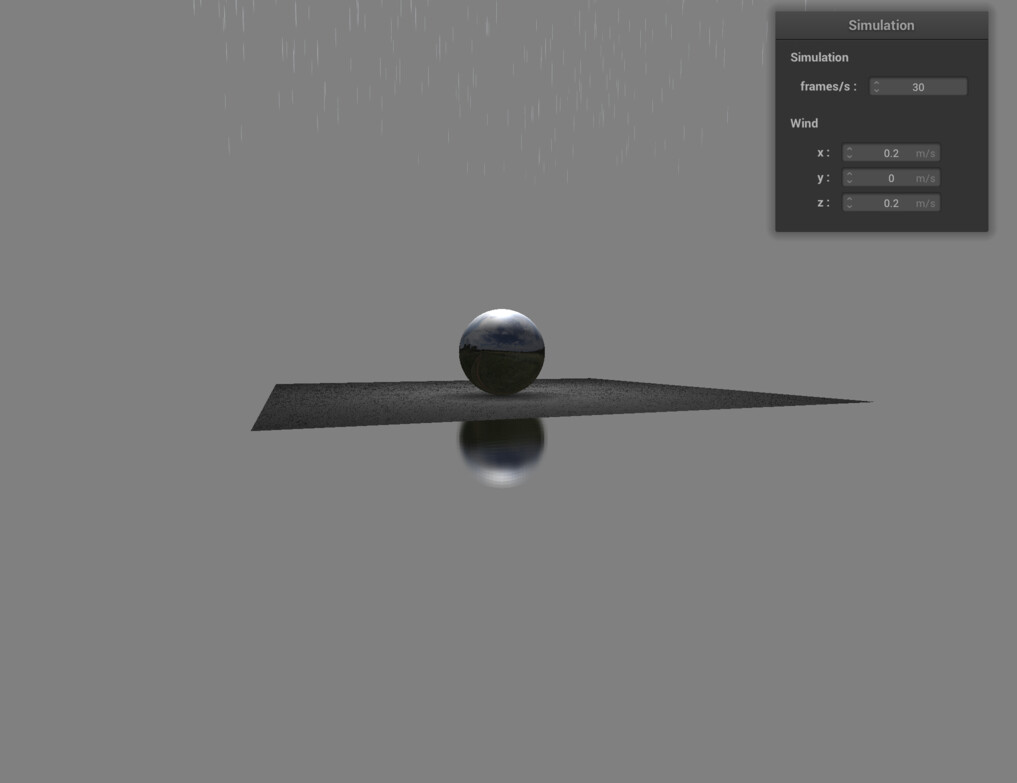

Reflection Tricks

There are multiple common ways in raster graphics to simulate the illusion of a reflective plane. Some of the most used in video games are 1. mirrored scene objects; 2. baked reflection cubemap; and 3. screen space reflection. We opted for the first option for a number of reasons: the obvious reason would be that it's easy to implement and gives a relatively satisfactory effect out of the box. In addition, there are drawbacks for the other options: baking reflection maps requires external tools and are only viable in cases where scene objects are stationary, and screen space reflection might not display the reflection entirely due to the object being so near the reflective surface. With relatively simple geometry to render and consequently acceptable performance costs, we went for the mirrored scene objects trick.

To ensure it looks correct, the shaders for the reflected object requires light sources and environmental textures be "inverted" in a sense. This can be easily achieved by doing lighting calculations and cubemap sampling using the "fake" position vectors as if it were upright, but computing glPosition using the reflected position vectors.

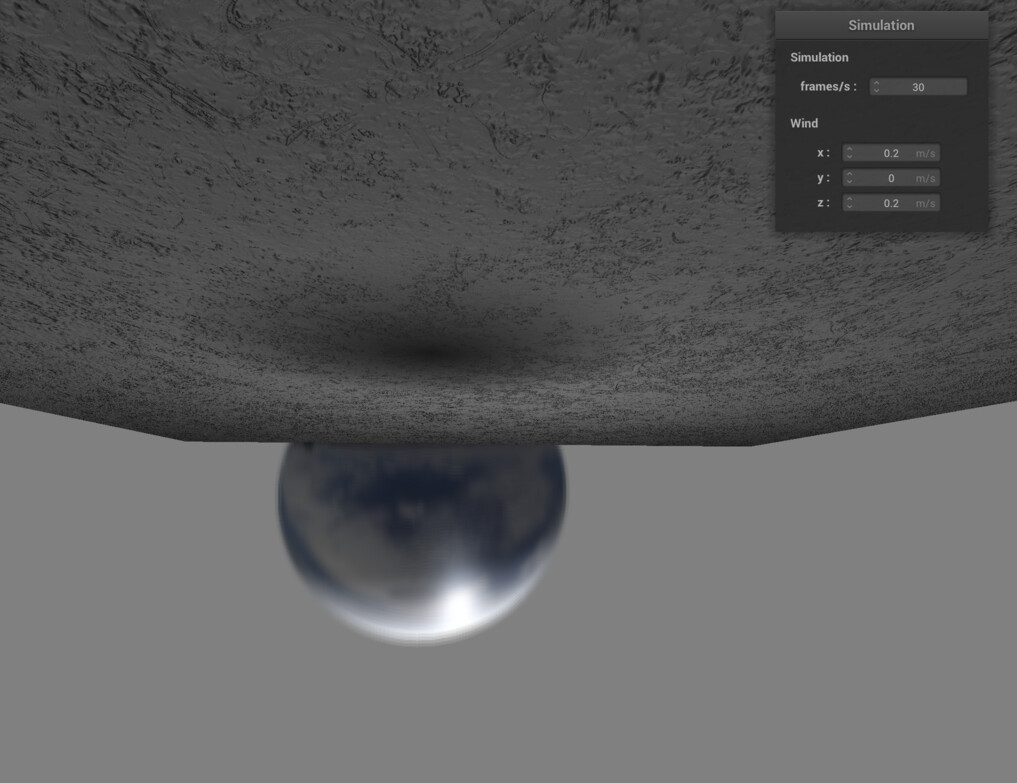

Screen Space Effects

One cherry on top is the blurred appearance of the reflection. This is achieved through screen space effects. Before rendering anything else, a new off-screen framebuffer is generated. Since the contents of this framebuffer will be blurred, the framebuffer is intentionally created with a fraction of the resolution of the regular viewport. The color component of the framebuffer is attached to an equally-sized 2D texture for use later; the stencil and depth components are created as RenderBuffer objects since they won't be accessed later. After binding to this newly created framebuffer, the reflected object(s) are rendered. We then switch to the screen buffer, and render the reflection "image" onto the screen framebuffer using a plane and a special blur shader. We then render the scene objects. The ground and the particles are rendered last as they all contain transparency.

The blur shader ignores vertex position inputs and maps them straight to the four corners of the viewport. A convolution kernel is applied at each pixel to blur out the framebuffer texture and achieve the desired effect. One drawback of this approach is the fact that the blurred amount is invariant to the scale of the reflection: this can most likely be remedied by incorporating the depth map of the off-screen framebuffer, and scaling the kernel sample offsets based on the depths at each point.

An interesting bug we encountered happened on high DPI displays, where the framebuffer size is twice that of the logical pixels. This would cause the image to display only at a corner of the window. To fix this, we made an additional call to the simulator object when creating the GLFW window to give it the accurate dpi-adjusted window size, instead of resorting to the default behavior of assuming a predetermined window size.

A major lesson learned is to take pages from video games, which are the culminations of years of head-scratching from raster engine developers. For example, for reflections, the three options were widely used in video games, and the advantages/disadvantages were clear. We can then choose appropriately weighing the pros and cons.

Results

References

Artist-Directable Real-Time Rain Rendering in City Environments

Contributions

Richard Yan: Project idea. Created project code skeleton from ClothSim codebase, implemented ground and scene object shaders, and screen space effects. Helped tuning appearance of raindrop and splash particles.

Qingyuan Liu: Implemented rendering of raindrops, animation systems for splashes and dynamic painting; Optimized particle simulation for performance; Setup the particle system.

Sher Shah: Wrote the dynamic wind code. Helped create shaders for the ground plane. Created the inital particle simulation.

Joie Zhou: Helped set up the dynamic ground plane texture map. Helped set up opacity and lighting shading of raindrops.